When you enter the state government’s industrial park in Dobbaspet, 50 km from Bengaluru’s city centre, you barely see any green. Rows of factory sheds, unending roads and dusty wind mark the area. In this dreary environment, Jacob Crasta’s CM Envirosystems’ 1-lakh sqft facility looks like an oasis, with lots of lawn and plants and trees.

Brought up in Mysuru, Crasta picked up his business skills in Mumbai during a three-month training programme with a laboratory equipment manufacturer in the late 1970s. “ I used to meet around 30-32 different clients every day to try and sell laboratory equipment,” he recollects. In 1981, he returned to Karnataka and established a laboratory equipment making unit in a small 5,000 sqft facility in the Peenya industrial area in Bengaluru.

A decade later, when India suddenly liberalised its economy, Crasta felt his business may not be able to survive global competition and started hunting for new business ideas. A promising idea finally struck him when the Kargil war happened in 1999. “There were sanctions on India and proper testing equipment could not be imported. We lost many soldiers because a number of telecommunication equipment did not work,” he says. Around this time his eldest son, Prajwal, joined the business, and together they decided to start making testing chamber for the defence and auto sectors.

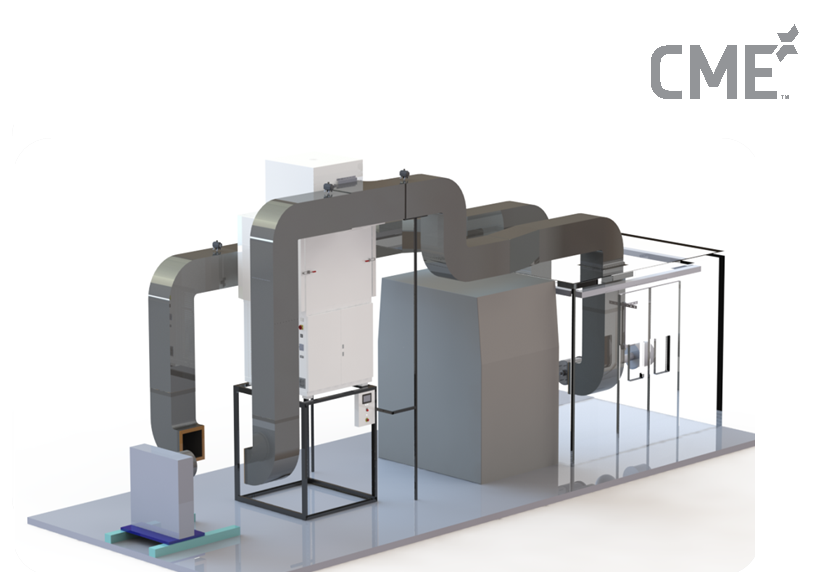

At its Dobbaspet facility, to which they shifted in 2008, CM Envirosystems now designs and manufacturers environmental test chambers that are used to simulate real environmental conditions such as temperature, rain, dust, humidity, and pressure. “We create an atmosphere from -80 degrees to 250 degrees Celsius for temperature, humidity levels that range from 5% to 90% and simulation of up to 1 lakh metres above sea level,” says Crasta. Components of fighter jets like Sukhoi, and the Agni and BrahMos missiles are tested in their chambers.

The company, which expects to have a turnover of Rs. 500 crore this year, also exports its machines to over 20 countries – including the UK and many South East Asian ones- and says it is often a direct competitor to manufacturers in Germany, Japan, and the US.

But it was difficult getting customers initially and making them trust a Made-in-India product. “No one trusts Indian companies. Although German and US-made products are very expensive, they would all go for that,” Crasta says. His son Prajwal, who has assumed the role of CEO, blames it on local companies that went for cheaper quality to become cost competitive. “Tenders comprise of 50% of the business, so there is a tendency to offer products at a lower cost. In 2006, we decided that if we had to survive and ensure companies trusted us, we had to invest in technology,” he says. And that’s what they did. Their machines are today sold at twice the price of any Indian competitor, but are still 30-40% cheaper than their US competition.

But the father and son say that few in the manufacturing sector have had CME’s luck. “Hardly 6% of all the sheds allotted in the 1970s and 80s in Peenya has survived. The children of many of those who set up factories are not interested in manufacturing. New entrepreneurs are not interested in this space. The land that I got for Rs.10 lakh an acre now costs Rs. 2.5 crore. Who has that kind of money!” Crasta says. This partly explains the dreariness of the Dobbaspet industrial park.

Prajwal believes the situation can get better if the Karnataka government steps in with the right incentives. “ The government should make it easier for young entrepreneurs to access land. If we think big, and see the world as the market, India and Indian manufacturers could do really well,” he says.